Meet Marisol

Part I

Perhaps you recognize Marisol or her sculptures. I didn’t at first. When I began researching her almost two years ago, I failed to remember that I had encountered her work long before: in 2016, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, where her sculpture, “Women and Dog,” from 1963, lives in its permanent collection.

Or maybe you’ve seen her monumental work, “The Party,” at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, a piece that lives up to its name with 15 freestanding, life-size figures and three wall panels. True to her singular style, Marisol’s fete features an assemblage of wooden elements that she carved by hand, as well as a rowdy assortment of found items—from clothes and shoes to a television set.

If not through a museum, perhaps you know her from reading the society pages in the 1960s, when Marisol palled around with Andy Warhol, and sold out shows at the famous Stable and Sidney Janis galleries. The press cast Marisol as an exotic enigma: born in Paris to Venezuelan parents, she spent her childhood traveling the world. When she was 12 years old, her mother committed suicide, trauma that made Marisol swear off of conversation, speaking only when spoken to—a silence she sustained well into adulthood after settling in lower Manhattan in the fifties. Over the decades, Marisol remained a fixture on the New York art scene, sometimes photographed on the arm of other artists like Willem de Kooning, but never marrying.

In her later years, Marisol developed Alzheimer’s disease, and her best friend, Mimi Trujillo, took on the role of her care partner, a heavy responsibility that included constantly stocking drawing materials so that the inveterate artist could continue to make.

In 2016, Marisol died of Alzheimer’s, and left her entire estate, including her personal archive and her art collection, to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York. The museum is still in the process of inventorying her records.

The last major exhibition of Marisol’s sculptures and drawings took the form of a thoughtful retrospective at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art in Tennessee, before traveling to El Museo del Barrio in Harlem, New York.

Closer to home, you may have seen her sculptures on view, in years past, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago or the Art Institute of Chicago. The latter boasts 25 works by Marisol in its permanent collection. Sadly, none of her work is currently on view at the Art Institute or the MCA. Which makes this art tour largely one of the imagination: together, we will trace Marisol’s footsteps through Chicago, and pay homage to her enduring imprint on the city.

Part II

Marisol is a more-than-meets-the-eye-type artist. She liked to let her sculptures, drawings and prints speak for themselves, lacing wit and satire into the scenes she set. Consider, for instance, the artist statement she wrote for the Stable Gallery in the 1960s:

“I like to make combinations that seem incongruous—wood with plaster—pencil drawing on wood but finally I put things where they belong—a hand at the end of an arm—a nose on the middle of the face—a hat on top of the head—a shoe on a foot—a foot on a leg—a breast on a woman’s torso—a mouth a little below the nose and a nostril inside the nose. Sometimes I also make horses and dogs and cats.”

Keep this dichotomy in mind as we move along: this sense that Marisol was interested in both disrupting and belonging. This tension between the odd and the familiar animates a lot of her work.

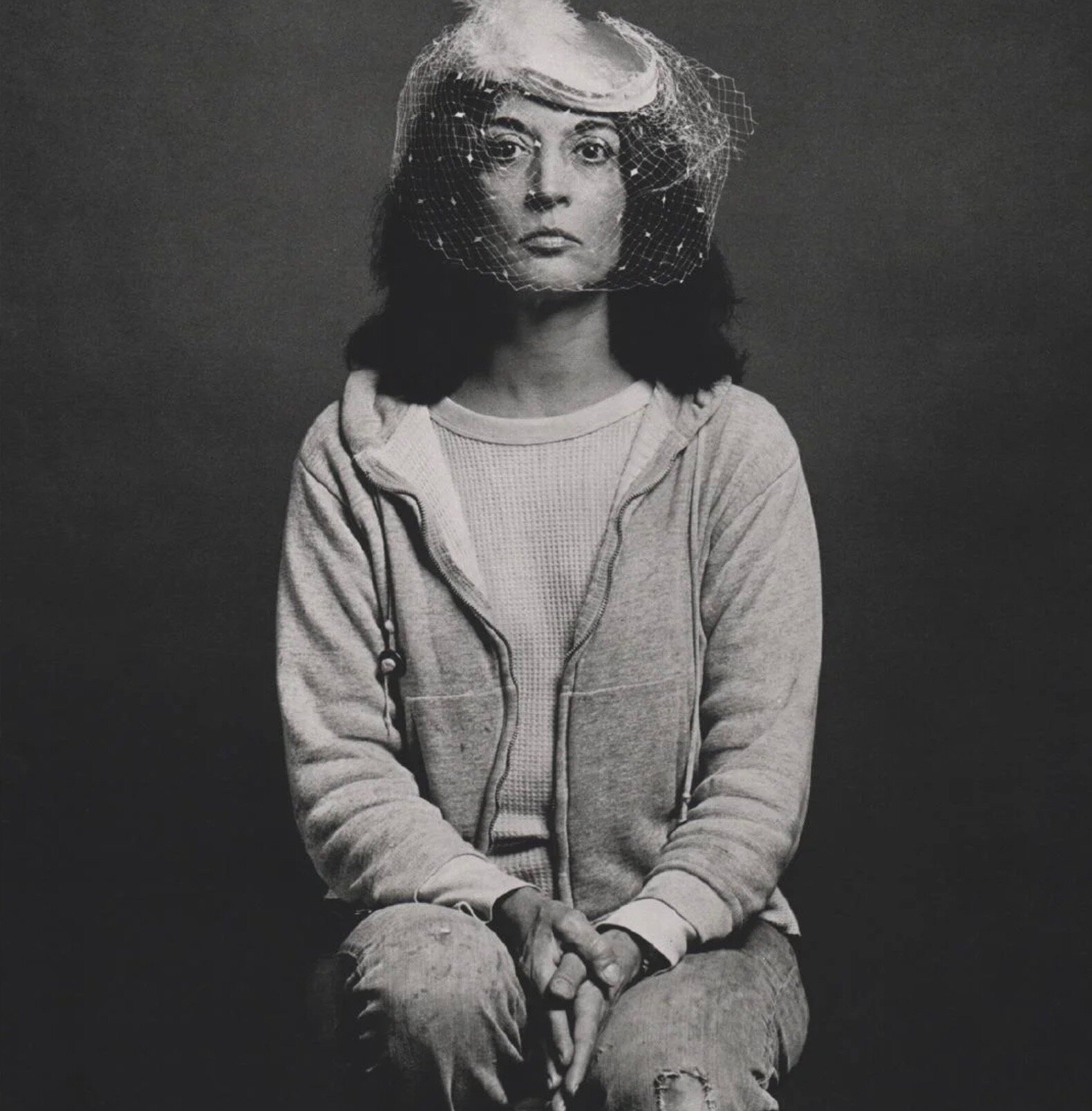

Gelatin silver print, 13 13/16 × 13 13/16 in. Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

Listen to MEET MARISOL Part I

Assemblage of four freestanding, life-size figures and a taxidermied dog, with painted wood and carved wood, clothes, shoes, and other accessories. Whitney Museum of American Art.

Assemblage of 15 freestanding, life-size figures and three wall panels, with painted wood and carved wood, mirrors, plastic, television set, clothes, shoes, glasses, and other accessories. Dimensions variable. Toledo Museum of Art. Museum Purchase Fund, by exchange. © Marisol/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Stable Gallery records, 1916-1999, bulk, 1953-1970. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Listen to MEET MARISOL Part II.

Harold Washington Library

Women Leaning Part I

Each of the four women in this life-size grouping are self-portraits of the artist; Marisol cast each face from her own.

Do they share the same expressions? Or different?

The first visage seems to be clenching her eyes closed, deliberately shutting out the rest of the world. The other three appear more relaxed, their eyes and cheeks slack with serenity as if resting.

I invite you to think or talk about the concept of a self-portrait: If you were having a portrait made, how would you want it to look? What would you want your portrait to capture about you?

Women Leaning Part II

As the only Marisol sculpture currently on view in Chicago, Women Leaning lives within a distinctly public context, permanently installed inside the central Harold Washington Library, greeting patrons as they exit the elevators on the 7th floor.

The women lean against a wall shared with a conference room. Their backs are to the open stacks of the 7th floor, stocked with books by Chicago authors, or classified as fiction, world languages, poetry and plays. Oriented west, they face the men’s restroom and the water fountain, which means a constant procession of people pass by the sculpture, although, as I’ve observed on multiple occasions, very few seem to pause and take notice of it.

The women don’t live alone. They share the 7th floor with other artworks: Together #2 by Jerzy S. Kenar (1998), standing opposite them and the elevator bank. Bronze busts of Gwendolyn Brooks (1994), Ernest Hemingway (1994) and Saul Bellow (1993) by Sara Miller hover steps away and Preston Jackson’s Life/Death Cart (1991) lives down the hall in a glass vitrine, after the stacks of short stories and fiction. Together, these sculptures seem to create an ecosystem of somewhat silent luminaries.

Originally, Chicago advertising exec and artist Edward H. Weiss purchased the sculpture for display in the creative department of his eponymous advertising agency, before donating it to the Chicago Public Library.

Women Leaning Part III

What shapes did Marisol use to build these figures?

How would you describe their postures?

Do they seem alert or tired?

Marisol was in her mid-thirties when she made this work. She was thriving as an artist, poised to represent Venezuela at the 1968 Venice Biennale. And yet, by being unmarried in the male-dominated New York art world of the 60s, social fatigue might have set in. Throughout her life, Marisol bucked societal expectations—choosing an independent path for herself—and yet, her life choices made her rub up against cultural constructs surrounding beauty and aging. Perhaps these leaning women bears the trace of such friction in their rigid postures, blocky silhouettes, and self-composure and -exposure. They seem comfortable in public, but a bit weary of the world. They know they are being observed but refuse to meet your gaze. Rigid bodies in rank and file, almost militaristic in their order. A subversive satire on the stereotypical representation of the feminine parade.

Women Leaning Part IV

In 2017, Women Leaning underwent repair and conservation work: at some point, a library patron swapped two heads, nicking a nose—an act noticed only after-the-fact.

Even now, some elements of the sculpture exist in a different state than Marisol originally intended. Compare the black-and-white archival photograph of Marisol and Edward H. Weiss in front of Women Leaning with the color pictures taken recently.

What do you notice about the archival photo? What aspects of the sculpture seem different now?

Look closely at the second face, specifically the right eye. It seems like Marisol originally decorated that eyelid, a detail which has not survived the decades.

Is something else missing?

In the archival photo, there appear to be two purses: the carved orange one on the fourth figure and on the first, a vintage purse dangling from a hook. It turns out someone swiped the original purse soon after its installation inside the library. The Special Collections librarian immediately contacted Marisol for instructions. Unfazed, she bought another at a thrift store and sent it to Chicago. The new/old handbag now lives in Special Collections alongside The Marisol Poems, a chapbook of poetry by Millie Mae Wicklund that features Women Leaning on its cover. Through a series of lyrical experiments, Wicklund adores Marisol from a distance, her words bordering on dubious devotion.

I imagine the missing purse filled with poems, including Wicklund’s “Homage to Marisol,” which begins and ends with the following stanzas:

I go out for a walk.

I look at the clouds. Are you Marisol?

Rain falls. Are you sorrow?

I look at a tree. Are you Marisol?

It barks at me. I run and it is no different from any other day of my life.

Are you required suffering?

No.

You might as well be the moon. You might as well be my birthday Which I wish every year to be filled with satisfaction. You might as well be the hinge of each culture hero’s narrative.

From Bangladesh back, what are we women supposed to be?

What business have I to make a voyage towards you?

Why do I explain my life through yours?

I put everything I have looked at in the poetry machine.

And off I’ll go again for a loaf of bread.

It makes its usual noises. Then suddenly a great fire breaks out.

Then a great bang and it collapses.

So it’s you who have stopped poetry.

Harold Washington Library, March 2019.

Listen to WOMEN LEANING Part I.

Listen to WOMEN LEANING Part II.

Listen to WOMEN LEANING Part III.

Photographer unknown, Harold Washington Library Special Collections file.

Listen to WOMEN LEANING Finale.

Arts Club of Chicago

Arts Club Part I

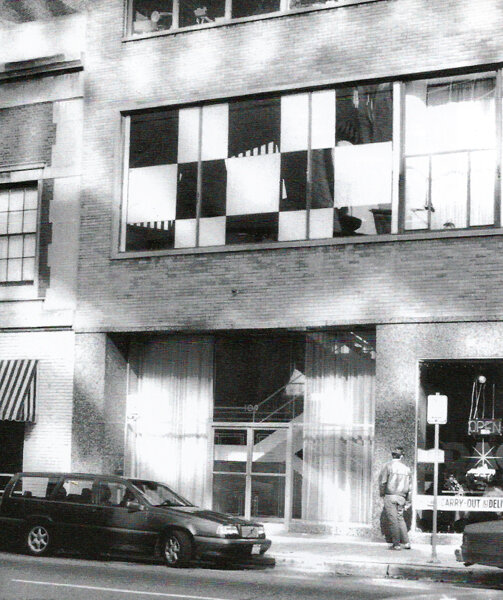

Chicago proved to be a landmark for Marisol; it played host to her first solo exhibition outside of a commercial gallery. The show, titled “Marisol: Impressions,” filled the prime holiday slot at the seminal Arts Club of Chicago, opening December 14, 1965 and closing January 15, 1966. Her large-scale sculptures and abstract drawings filled the sleek gallery Mies van der Rohe had designed for the Arts Club at 109 East Ontario Street. Marisol attended the opening reception; she had never been to Chicago before.

True to the times, the exhibition evolved patiently over correspondence. Starting with a curatorial wish list, the show took shape with loans secured from both Marisol’s gallerist—Sidney Janis—as well as a handful of private collectors, the majority of whom hailed from Chicagoland. A handful of institutions and individuals turned down the Arts Club’s invitations to send their Marisol sculptures, with several citing the works’ delicacy: the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, NY—the first museum to acquire her art—cordially declined the request for Baby Girl and The Generals. The reason given: the two large-scale works were “not permitted to travel.”

Have you ever been involved in an event where the original plan was more ambitious than the ultimate outcome?

Or have you ever resisted loaning something out for fear it might return damaged?

Arts Club Part II

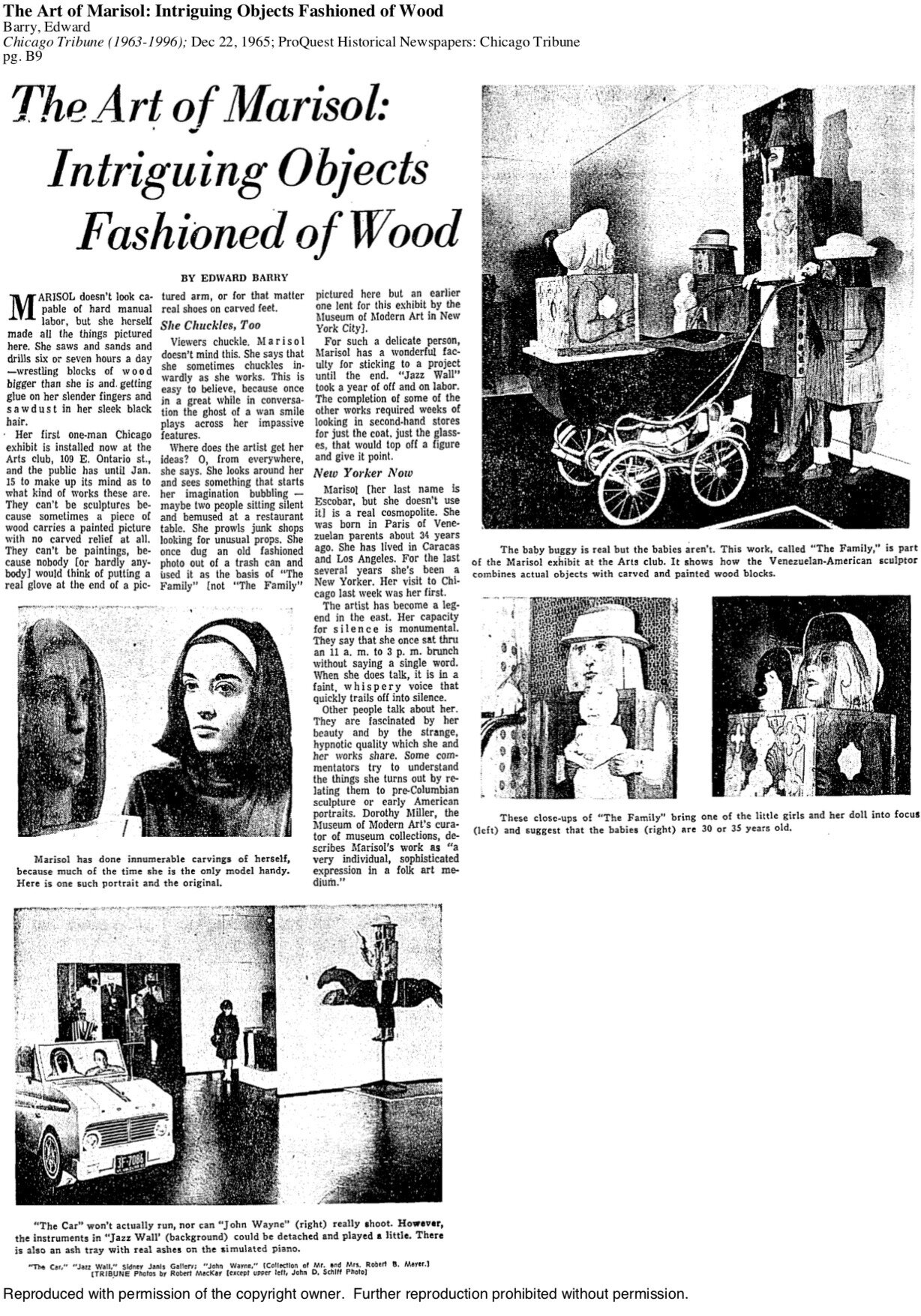

“Marisol: Impressions” proved to be a banner Chicago debut for Marisol: reporters fanned the flames of her mystique and enticed readers to attend the show. Edward Barry of the Chicago Tribune cast the exhibition as a riddle to resolve: “…the public has until Jan. 15 to make up its mind as to what kinds of works these are. They can’t be sculptures because sometimes a piece of wood carries a painted picture with no carved relief at all. They can’t be paintings, because nobody (or hardly anybody) would think of putting a real glove at the end of a pictured arm, or for that matter real shoes on carved feet.”

Barry seemed perplexed by Marisol’s inventiveness.

Do you find her assemblages strange?

Do they seem to defy definition, as Barry believes?

This ambiguity—reframed as the question of whether Marisol had realism or satire or a mixture in mind—made some squirm. Chicago Tribune photographer Robert MacKay covered the exhibition and described the scene as such: “The Car won’t actually run, nor can John Wayne (right) really shoot. However the instruments in Jazz Wall (background) could be detached and played a little. There is also an ash tray with real ashes on the simulated piano.” Curator Marina Pacini interprets the ambiguity inherent in her sculptures as an invitation: “Leaving room for the viewer to bring their ideas and history to bear allows for a richer engagement. It also makes you stop and look more closely.”

Do you agree? Do her sculptures make you stop and study?

Arts Club Part III

The Arts Club exhibition included some of Marisol’s greatest hits from her first decade as a professional artist, including The Family with its real stroller, John Wayne and its celebrity satire and the social commentary of The Car.

Two pieces sold: Self-Portrait and Jazz Wall. The late Chicago collector Ruth Horwich purchased the jazz scene, and left it to the Art Institute. The President of the Arts Club at the time, Rue Winterbotham Shaw, wrote Marisol a glowing letter after the show closed: “The attendance was enormous so you should be happy when you think of your first one-man show in Chicago.”

Behind the scenes, a bit of a dispute erupted over accounting: Sidney Janis challenged the commission split, saying he never authorized the “special discount” given to the Arts Club members who purchased pieces.

Arts Club Finale

Marisol’s Chicago debut occurred at the height of her practice of sculptural assemblage, which found her sourcing and sculpting distinctive elements—some were already existing objects—into composite figures that personified her thoughts on sixties-era America. Ultimately, the personalities and groupings she imagined transcended the sum of their parts and spoke to wider issues coursing through society. I invite you to think about how you would piece together a portrait of America today. Using magazines or newspapers, pick out some elements that speak to you and build a character or characters from those clippings. Once complete, think about how you would introduce your collage to a friend or relative.

The fifth location of the private club and public exhibition space, with the interior designed by Mies van der Rohe in 1951.

Listen to ARTS CLUB Part I.

Installation view of The Arts Club’s 40th anniversary exhibition Cubism—Continuing Tradition, 1955.

Wood, metal, graphite, textiles, paint, plaster and accessories.

Listen to ARTS CLUB Part II.

Listen to ARTS CLUB Part III.

Wood, mixed media. 104 x 96 x 15 inches. Collection of Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, Julianne Kemper Gilliam Purchase Fund and the Debutante Ball Purchase Fund.

Listen to ARTS CLUB Finale.

Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

Six Women I

What is unique about each of these women?

What are the women’s most distinguishing features?

How would you describe their faces? How do they vary?

Does color seem important to their presentation? If so, what colors?

Recalling Marisol’s penchant for unexpected compositions, this sculpture is defined by a distinct anatomical geometry: six carved heads with various plaster features share a trio of torsos. The bodies are positioned close to one another, suggesting an intimate grouping.

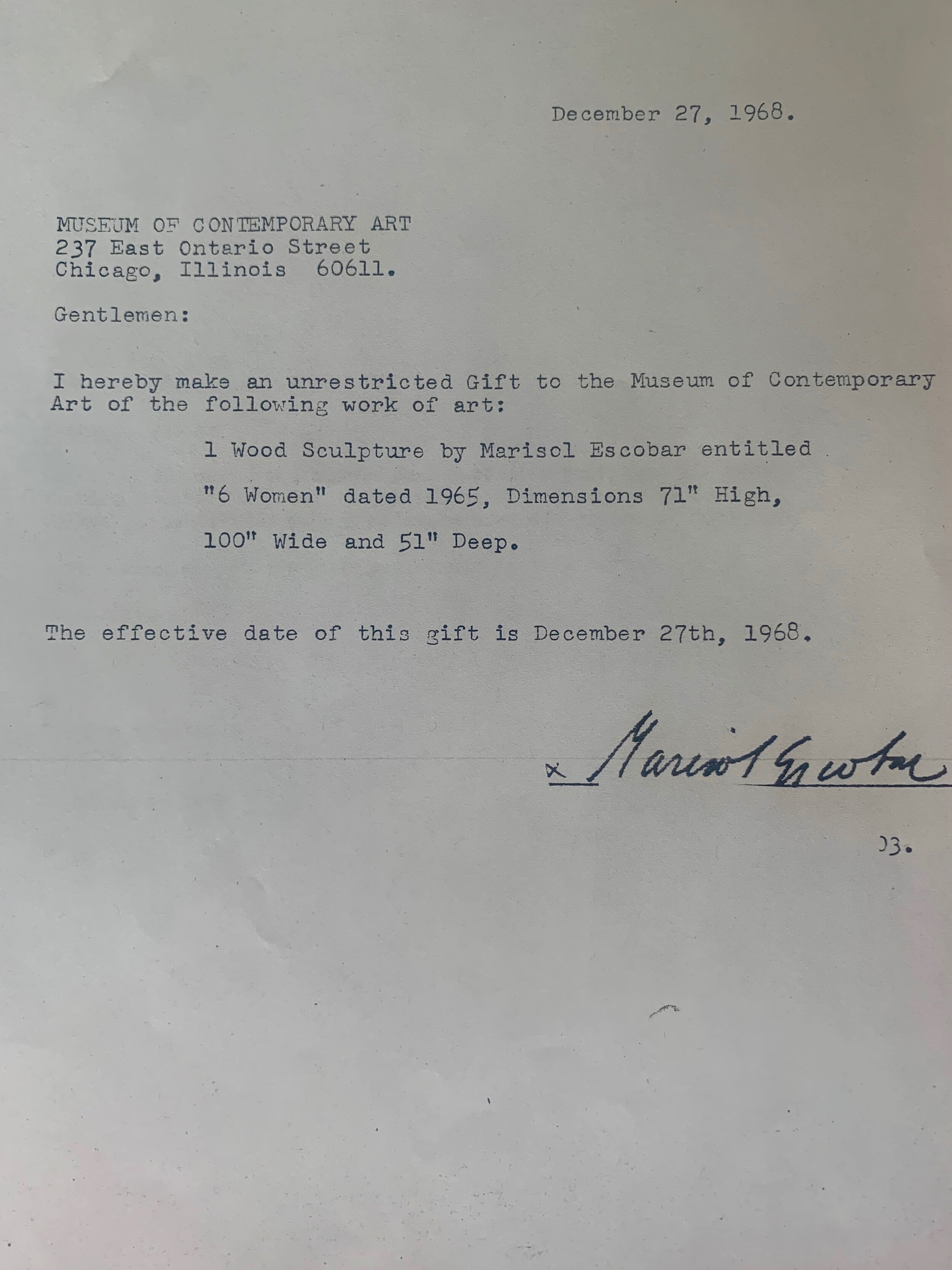

In 1968, Marisol gave Six Women to the MCA, a gift which initiated the museum’s shift from a Kunsthalle hosting roving exhibitions to a collecting museum exhibiting its own holdings. Within a year of its installation in Chicago, the sculpture began traveling (in five crates no less): first to the Cedar Rapids Art Center in 1970 and then on to the University of Iowa Museum of Art, where it remained for a lengthy loan of nine years. Since returning to Chicago, Six Women has been on steady rotation in the galleries (though unfortunately not now). Including the 2013 exhibition exploring the reciprocal creative friendship between Marisol and Andy Warhol.

I invite you to invent a story about these six women. What do they do as individuals? Are they artists? Or professionals? Or mothers? All or none of the above? How do they know each other? Are they friends? Or co-workers? Or did they just meet? Where are they now and where will they go next?

Six Women II

What different art techniques did Marisol use to fashion these women?

Are all elements of the sculpture attached? If not, which seem unfixed? Or out of proportion slash step?

The shoes!

Six women but only three pairs of shoes: two pairs of black shoes, one with suede bow laces and the other with buckles; and tennis shoes in red and purple. All showing signs of real wear and tear. Or as a conservator reported in 2012: "The shoes were not conserved, condition stable."

The shoes have always been an interesting sticking point in the sculpture’s lifespan. According to museum records, Six Women debuted at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1966… with four pairs of shoes. The file for the sculpture does not contain an inventory of the piece when it arrived in Chicago two years later, but it does include a note from curator Judith Tannenbaum: upon its return from Iowa, she notes: “Three pairs of shoes were included instead of four as shown in photographs of the installation at Sidney Janis Gallery…”

Did one pair of shoes go missing en route between Iowa and Illinois, or did the Chicago version of the installation never include four pairs?

We may never know, but regardless, the shoes remain an object of fascination to many museum visitors. A log of incident reports suggests people have moved the shoes on multiple occasions—kicking, nudging, even sidestepping them.

Marisol Restaurant

When the MCA reopened in 2017 after its $16 million revamp, the sparkling new space, designed by Johnston Marklee, included a fine-dining destination hatched by Chicago chef Jason Hammel of Lula Café in Logan Square. To commemorate the museum’s first acquisition, Hammel named his new concept Marisol. The menu shifts seasonally, but often features the Marisol Salad, a mix of butter lettuce, apple, dill, macadamia nut, pecorino, and the mysterious “natural food salad dressing,” as Marisol described it in the MoMA Artists’ Cookbook published in 1977.

Wood, paint, mirrors, shoes, formica, and plaster. 69 × 105 × 52 in. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift of the artist, 1968.1. Photo by Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

Listen to SIX WOMEN Part I.

Photo courtesy of the University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City, IA.

Object file for Six Women, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Adelaide de Menil, courtesy of Acquavella Galleries, New York.

Photo by Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

Listen to WOMEN LEANING Part II.

Listen to MARISOL RESTAURANT.

Art Institute of Chicago

Jazz Wall Part I

What are some of the first things you notice when you look at this sculpture?

What are these figures doing?

Where might they be performing?

What kind of music do you think they are playing? What gave you that clue?

What is distinct about the way Marisol depicted this scene?

Jazz Wall debuted as part of Marisol’s second solo exhibition at Stable Gallery in 1962. Also present: John Wayne, her comical sculpture depicting the Hollywood actor atop a galloping red horse, pistol at the ready. Flash forward three years and the pair would appear again in Chicago. More on that on the Arts Club page.

Back to the Stable exhibition of which art writer Lawrence Campbell reported: “viewers came at the rate of two thousand a day—more on Saturdays. Her visitors included not only everyone who counts in the art world, but the kind of people one does not expect to find in an art gallery—mothers with five children, for example. Children are among Marisol’s most loyal fans.” Do you think kids have good instincts for assessing art?

Critics at the time considered the show from a variety of angles, (quote) “from serious discussions of her sculptures and her relationship to Pop and other movements to a focus on her looks,” (end quote) as curator Marina Pacini wrote. Her appearance seemed important because Marisol made cameos in many of her pieces: as a passenger in the sedan depicted in Ford (1964) and as one of the male musicians in Jazz Wall. Marisol explained this self-motif as the result of both practical and philosophical factors: often working late at night, her face was the only one available to cast in plaster; she likened making models sit for portraits as a form of torture; she felt no matter how simple the subject, every work by an artist becomes a reflection of themselves. By casting her own face differently every time, Marisol explored a spectrum of identities. Her presence becomes a foil for feminist discussion.

Jazz Wall Part II

Jazz was an important part of Marisol’s life. Moving to New York straight from high school, she started hanging out with the Abstract Expressionists, a creative clique that included Willem de Kooning. Memphis Brooks curator Marina Pacini described de Kooning as a formative figure in Marisol’s early days in Manhattan: “For me, one of the most fascinating parts of her biography is her relationship early on with de Kooning. He was her lover for a time. She was very young when she came to New York—eighteen or nineteen. She found her way to the Cedar Tavern, where she met the Abstract Expressionists, including de Kooning. She quickly adapted to the bohemian lifestyle. Having had an over-protected, privileged background, it was a liberating experience for her. She smoked lots of pot at the time. They’d go to the Five Spot to hear jazz after hours; they’d hear David Amram’s quartet, for instance. It was a place to meet people, to fall in love. There was a confluence between music and visual art at the Five Spot; it was kind of the [Abstract Expressionist] equivalent of CBGB and the punk movement.”

I love to imagine de Kooning and Marisol traipsing around Lower Manhattan, listening to jazz, discussing art, carousing and carefree. Those days serve as a counterpoint to their shared shift decades later: In a fascinating turn, de Kooning also had Alzheimer’s disease as he aged, however his experience of the disease is cast by curators as a heroic triumph of his creative will over cognitive decline, whereas Marisol’s last decade with the disease remains undocumented. I want to make space for a conversation around creativity happening with—not in spite of—cognitive fragmentation.

In my research, I have interviewed some of the people closest to Marisol in her later years, including a Georgetown student named Greg Svitill who, while focusing on her work for his senior thesis, cold-called the artist, then in her seventies. And she picked up! And they became friends! Greg recalls stepping foot inside her Tribeca loft and often being greeted by one of three soundscapes: Jazz, Jennifer Lopez or National Public Radio. I now think of this anecdote as a loop back to Jazz Wall.

Jazz Wall Part III

Jazz Wall offers the opportunity to think about how music stoked Marisol’s artistic practice. I invite you to explore this influence for yourself by putting on a jazz playlist and picking up a paintbrush (I recommend watercolor or acrylic paints for this activity, because they are so fluid like jazz). Try painting a figure—a musician, a dancer, a friend, or a self-portrait. How does the figure flow with the rhythmic twists and turns of the music? Shift between different sized paintbrushes and pieces of paper. How does scale affect your expressions? Enjoy, as Marisol did, the melding of music listening and art making.

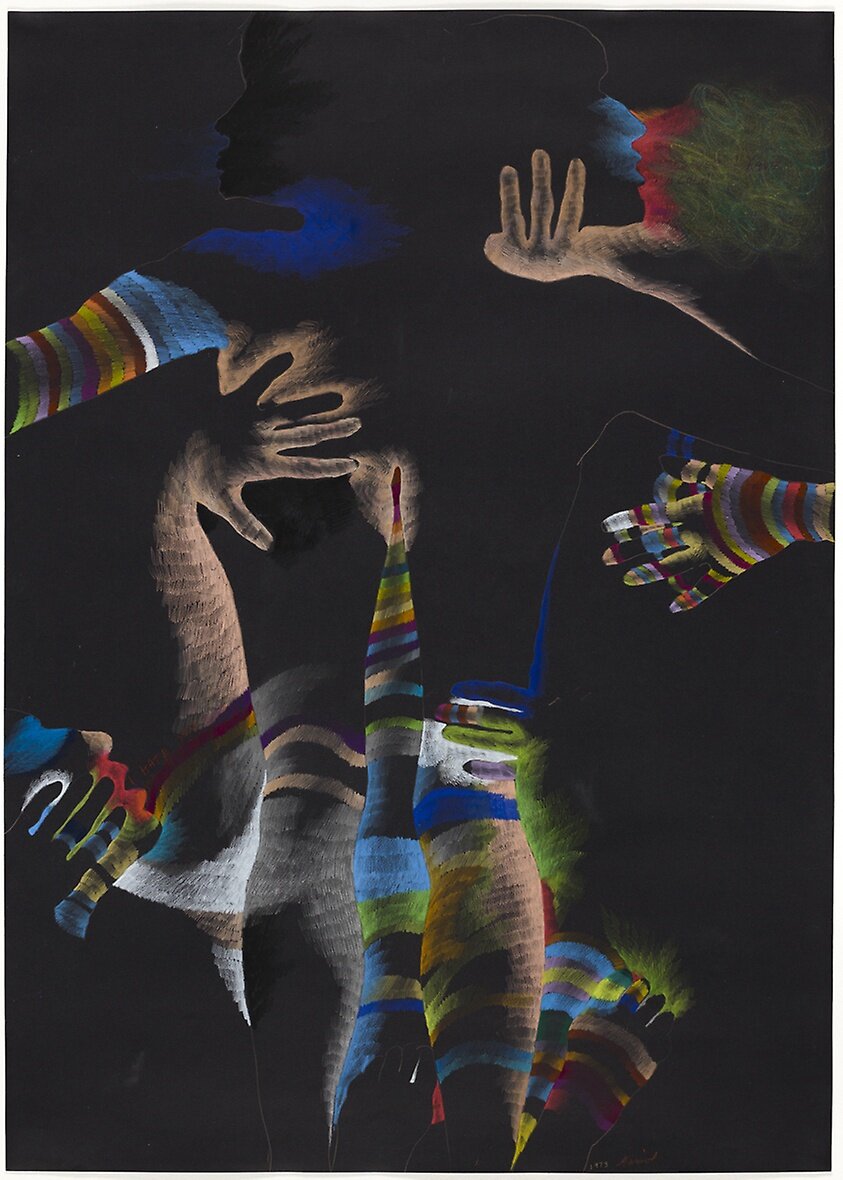

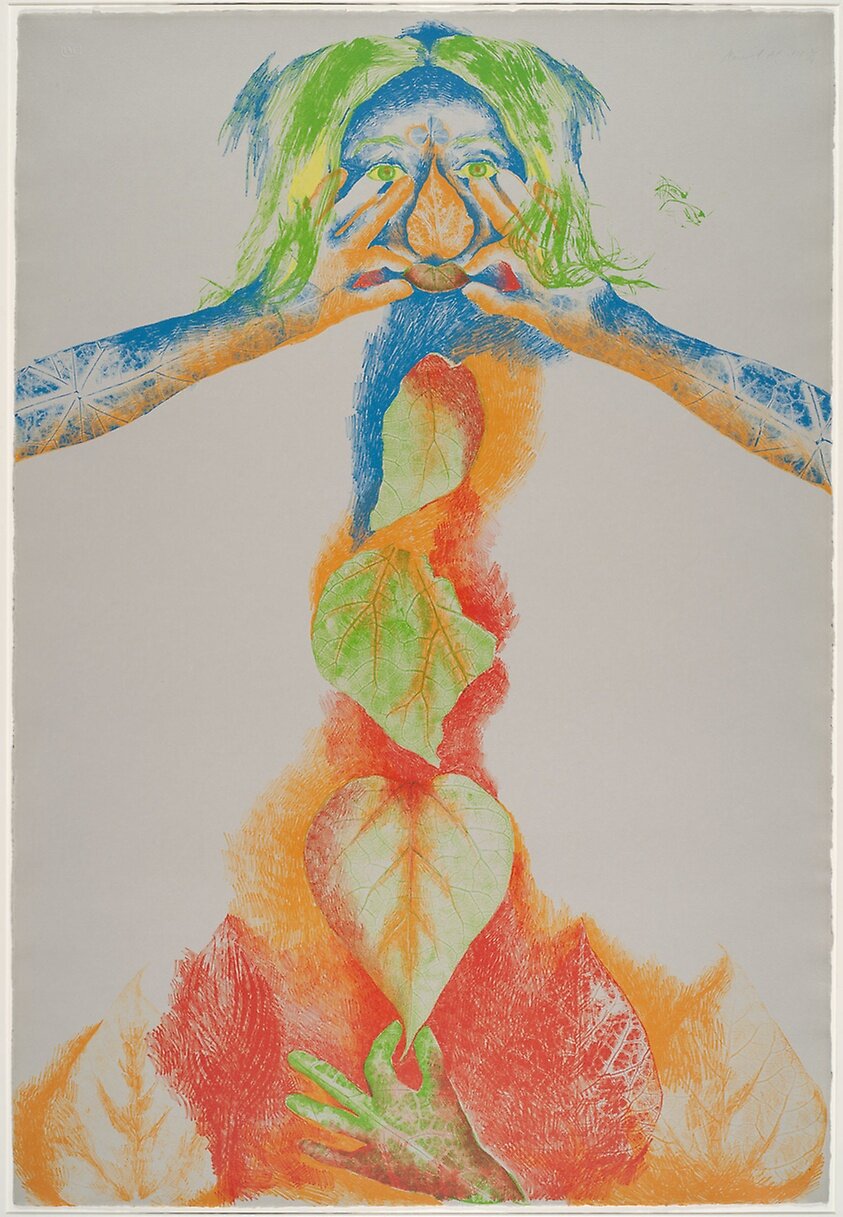

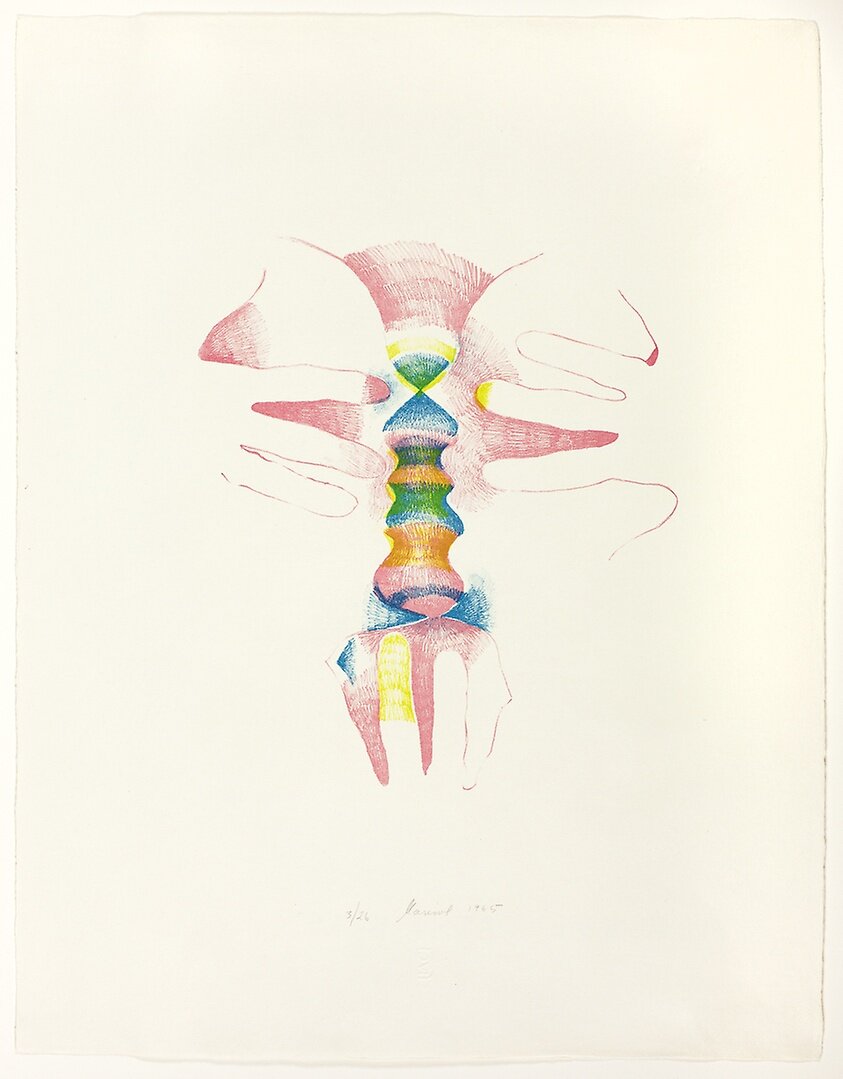

Art Institute Finale

In addition to Jazz Wall, the Art Institute has collected a stunning selection of Marisol’s drawings spanning the sixties and seventies. Her work shifted a lot in those decades, from the satirical, sometimes ambiguous social commentary of her sculptures to the more directed, assertive drawings of the seventies. Once again, I turn to curator Marina Pacini and her thoughts on this shift within the context of Marisol’s oeuvre: “There are probably several reasons for this, not the least of which is the changing zeitgeist. But she also was clearly rethinking what her art should be about and what it should look like. For an artist who was already accustomed to looking inward, in the 1970s she seems to have gone deeper into very personal areas that were highly charged. The obvious anger in the works on paper, the suggestions of danger in some of the fish sculptures, and the brutality of the masks are very telling. But she ends the decade with ‘Artists and Artistes,’ a study of creativity in old age. There is a generosity of spirit for others that appears in the late works of the 1980s and 1990s relating to people on the fringes, the poor, hungry, and Native Americans, that attest to her empathy and sympathy. She produced a remarkable body of work that celebrates humanity while also acknowledging its shortcomings.”

At her core, Marisol was an empathetic person: she responded to the emotional landscape swirling around and within her, inventing distinctive forms and modes through which to express herself through art. She sketched this instinct in a 1965 interview with the art critic Grace Glueck. She begins by explaining why she shifted from working in the painterly style of her mentor Hans Hofmann, turning instead to sculpture: "It started as a kind of rebellion. Everything was so serious… I was very sad myself and the people I met were so depressing. I started doing something funny so that I would become happier and it worked. I was also convinced that everyone would like my work because I had so much fun doing it. They did."

I invite you to scroll through the Art Institute’s collection of Marisol drawings and prints.

How do you feel when you look at these drawings?

Are those feelings different than your response to Jazz Wall?

Do you recognize certain forms or shapes in the drawings? If so, what meaning do they seem to convey in this context?

Did you notice the titles? How do they affect the way you understand her drawings?

Wood, found objects, paper, and paint on wood. 95 x 107 x 14 in. Gift of The Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Foundation. Copyright © Estate of Marisol.

Listen to JAZZ WALL Part I.

Listen to JAZZ WALL Part II.

Image courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery Digital Assets Collection, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. © Estate of Marisol / Albright-Knox Art Gallery / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Jason Mandella.

Listen to JAZZ WALL Part III.

Colored crayon and pencil on black wove paper. Restricted anonymous gift. Copyright © Estate of Marisol.

Listen to ART INSTITUTE FINALE.

Color lithograph on gray handmade woven paper. Collection acquired through a challenge grant of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Dittmer; restricted gift of supporters of the Department of Prints and Drawings; Centennial Endowment; Margaret Fisher Endowment Fund. Copyright © Estate of Marisol.

Color lithograph from three stones on white woven paper. Collection acquired through a challenge grant of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Dittmer; restricted gift of supporters of the Department of Prints and Drawings; Centennial Endowment; Margaret Fisher Endowment Fund. Copyright © Estate of Marisol.

Lithograph on ivory woven paper. Collection acquired through a challenge grant of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Dittmer; restricted gift of supporters of the Department of Prints and Drawings; Centennial Endowment; Margaret Fisher Endowment Fund. Copyright © Estate of Marisol.